Inside the Havasupai Reservation: What it’s like working locum tenens for the Indian Health Service

March 4, 2026

Halfway down the Grand Canyon sits an ancient and solitary community. An eight-mile trek on foot or a helicopter drop-off is your only way in. No roads even come close. Some 640 souls call it home. It is the heart and center of their homeland, 295 square miles of stark, stunningly beautiful terrain and shimmering waterfalls. The waterfalls give the people their name. Havasupai means “people of the blue-green waters.” The place? The Havasupai (hah-vah-soo-pie) Indian Reservation and the village of Supai.

Caring for the Havasupai community

Family medicine physician Dr. Christine Kramer first visited Supai as a tourist back in 2002. When she heard the Indian Health Service regularly helicoptered locum tenens physicians in to treat the Native Americans there, this family practitioner jumped at the chance to be considered for what she was sure would be an adventure.

Semi-retired, but still working part-time at a practice she helped create and doing part-time locums, Dr. Kramer keeps an eye out for adventurous assignments. She has also worked locum tenens for the Indian Health Service in Shiprock, New Mexico, and in Cortez, Colorado. In Cortez, her patients were Native Americans living outside the reservation. The Havasupai people in the Canyon, in contrast, have resisted assimilation into outside culture for nearly 500 years.

That alone made the assignment fascinating. But there’s so much more that makes treating these patients, as she has in total six times over the years, transformative—the Canyon itself.

Why physicians choose to work locums with the IHS

It’s one of the most beautiful places in the entire world. The privilege of being in the Canyon and taking care of the Havasupai people, and just feeling the history of it. I don’t know how to describe it. It’s just amazing.

“That’s what kept me going back. I loved the adventure of it, I loved being in the Grand Canyon. These people have occupied that village for more than a thousand years. They have attributes that are unique, including this understanding that they’re the guardians of this incredibly beautiful place.”

Being a “guardian” resonates with the family practitioner. She chose a career in medicine due to disillusionment over the insensitive care her mother received upon contracting lung cancer. “I felt I could do better,” she says.

Dr. Kramer started med school later than most at 34, a wife and mother of three boys. “We weren’t wealthy people, but my mom gave me six thousand dollars—I think that was my inheritance—and I said, ‘I’m putting this towards school’. That’s what made me want to do it, because I felt like I could do better.”

That guardianship is on display to all who see her work during her two-week stints treating the Supai people.

There are more ways to give back: Learn how you can serve a medical mission

Life and practicing medicine in remote Supai

“You’re working 24/7, you’re the only physician onsite,” Dr. Kramer says. She teams up with a full-time public health RN and a full-time substance abuse counselor, providing much-needed continuity between physicians. The villagers, she explains, “have all the problems of any of the Native Americans who live on reservations, and then some. Their major health problems are things like diabetes, hypertension, a lot of obesity, acute illnesses, colds, flu, sinus infections, that kind of stuff.” Subspecialists working locum tenens for the Indian Health Service fly into the Canyon for short stints, and she makes sure patients in need see the eye doctor, dentist, psychiatrist, or whoever the new arrival is.

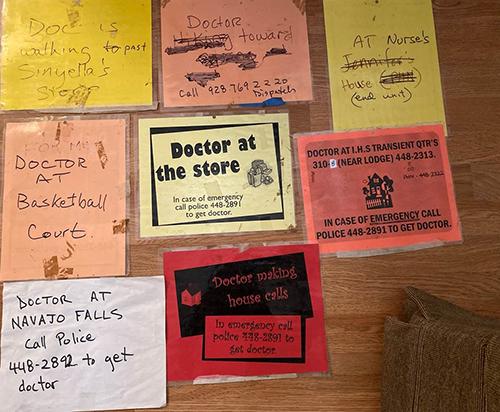

Tribal leaders take every precaution to ensure the healthcare professionals’ safety. “You’re working pretty closely with the police, particularly after hours and on weekends, because this is a dry community, and intoxication with both drugs and alcohol is common. A reservation is a very socialist community where every tribal member gets a paycheck once a month. After the paycheck comes, it's usually a pretty tough weekend because they manage to get plenty of alcohol and drugs down there in the Canyon. There’s a lot of mental illness, a lot of depression, a lot of domestic abuse and violence.”

It is definitely not an assignment for anyone hoping to take a vacation.

“It’s an emotionally taxing job,” she says. ”There’s just a lot of stuff going on. We have a Kubota, which is kind of like a big ATV, an ambulance that you drive around the village, and you may have to go pick someone up at their home and bring them into the clinic. You’re triaging any seriously ill or injured person who needs to be evacuated by helicopter."

A couple times a week, you’re going to have to call for medical evacuation. That’s what a day is like. And then, people might ask you to treat a horse or a dog.”

What it's really like: Working locums for Indian Health Service

Guests of a sovereign nation

With the tribal elders’ approval, Dr. Kramer was able to have immediate family and a few close friends join her to alleviate the hectic pace and the stress that are part of the job, and their presence has proven delightful. They’ve stayed with her in the two-bedroom apartment made available to healthcare providers like her. But that courtesy shouldn’t be taken for granted.

A contract worker, though not a doctor, she explains, abused the reservation’s hospitality by bringing a large contingent of friends into Supai, where they camped on the front lawn of the medical personnel's sleeping quarters. Because the spectacular waterfalls and breathtaking landscape attract thousands of visitors each year, the Havasupai leaders enforce a strict limit on the number and activity of tourists, such as: no day-hikers allowed, camping restricted to a three-day/four-night stay at the limited campsites situated two miles from the village, campfires not permitted, and reservations required as far out as two years in advance.

Outsiders camping in the village itself is a monumental breach of respect for the Havasupai, a sovereign nation.

Dr. Kramer views her chance to serve in Supai as a privilege. “I’m a guest here. This is their land; this is their treasure. I always want to be respectful about the tribe and how they do things,” she says.

One of the really important functions of that clinic is to provide healthcare in the tribal setting, not in a white person’s setting. The point is they deserve medical care near their home, responsive to their needs. That’s really important.

She adds, “It’s really good to be part of that.”

Working as a locum tenens in the remote Havasupai Nation offers a deep sense of purpose, as you care for a close-knit community with limited access to care. Learn about the Havasupai people and how you can make a difference, too.

Are you ready for a locum tenens adventure? Give us a call at 800.453.3030 or view today's locum tenens job opportunities.